The Perception of Kuldiga

in the Memory of Jewish Ancestors

by Eric Benjaminson

In memory of Bernhard, Joseph, Esfir, and Ruth Benjaminsohn (Kuldiga, Aizpute, Riga)

· I can only speak for myself and my family, but I hope that there are areas of agreement between our perspective and that of other descendants of Kuldiga Jews

· My paternal grandfather and many previous generations in my family were born and/or lived in Kuldiga, beginning in the early 18th century

· I believe, and I heard my grandfather say, that their lives there until the 20th century were measured and in some ways idyllic, with certain advantages over the lives of other Jews who lived deeper in the Czar’s Russian Empire

· In town, they lived lives as tailors, musicians, and general store owners; earlier, they worked on German estates, perhaps in the lumber trade and in distilleries

· Many of my ancestors in fact were professional violinists, and this appreciation for the memory of music in my family makes me personally interested in any future connection of the former synagogue with music

· They and other Jews made up fully half the population of Kuldiga until the 20th century. My ancestors served as officers of the synagogue (one as Treasurer), others provided housing for Russian soldiers, and still others served on the road paving committee of the city. One of my great-uncles was a Guild merchant who had direct contacts with Czarist officials on behalf of all the citizens of the city

· Given the history of the 1940s, my family was fortunate enough to have, in most cases, emigrated to South Africa or the United States by the year 1920. Others, however, chose to seek their economic betterment in Liepaja and Riga, where they were caught by the Nazi invasion.

· Of those relatives who went to South Africa, especially my great-grandfather and grandfather, until the Second World War they returned on visits to Latvia several times. Clearly family ties drew them back, but the perception they had of the town cannot have been negative

· Their memories of the town were tied directly to their mental picture of “Courland”. Courland was a word I heard often as a child – “Courlandish weather”, the forests and rivers of Courland, our relatives in Courland. Many of my relatives were buried in the U.S. in grave plots arranged by the Courlander Society. My great-grandfather, a professional musician in South Africa, arranged a series of concerts to raise relief funds for Courlandish Jews during the First World War. Home was clearly home.

· But with all that, their memories were deeply affected by the Holocaust. Kuldiga became a mental image of dark and mysterious horrors, of the imagination of torture and death and uncertainty for those relatives that had been caught there by the war. The decade from 1940 to 1950 was filled with attempts to understand what had happened and whether there were any survivors. As time went on, and as it became clear that there were no survivors, the losses transformed themselves into memory.

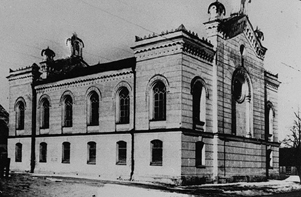

· Memory has always been an important concept for Jews, given our common heritage and ties to centuries of common histories and legends. The Holocaust forced a new role for memory, as we tried to use memory to provide a certain honor and remembrance for those who had died. The synagogue project in Kuldiga is a microcosm of that effort, and we greatly appreciate the role of the City of Kuldiga. In my own view, what is most important about the synagogue renovation is that it provides a site where the pre-war Jewish population is memorialized, perhaps through a name book or plaque, while creating an environment that honors their presence in what was the center and the heart of the now-destroyed community.

|