Nach der Erinnerung /

Memory, memorials, images.

by Sven Eggers

|

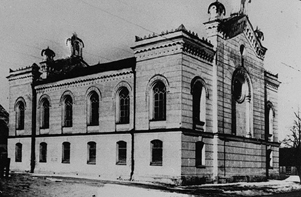

The original lecture in German 1. intent 2. to remember, to repress 3. to forget, to lose 4. victim and perpetrator: objects in museums 5. identity 6. memorials 7. be concerned and come to terms 8. to sense, to understand: art 9. images and the unrepresentable 10. the photo of the synagogue 11. re-capitulation and end 12. appendix: books and libraries 1. intent How to remember what isn't your own experience, but for what we feel a need that it is remembered? And when it is unimaginable? Or too tough to bear? How do memorials work? What do they show? How does its transmission work? Does memory hinder understanding? Is the oblivion needed? Which images do we have in Kuldiga? Where are they coming from? Do relics spoil the ideas of the perpetrator? “Never fascism again” – but how? We point our finger to it. There. There it is. What? Christa Wolf wrote: We were there now. We will have been here now. Somewhen those, that who have a remembrance of their own experience of the Shoa, will have disappeared. Already most of the participants of this symposium belong to the second or third generation, which are formed “ineradicably” by the Shoa, as James E. Young writes. To remember the catastrophe means for them to remember something transmitted. How do we cope with that several times transmitted experiences, how do we cope with second hand memory? “It involves a generation that can't or isn't willing to distinguish the remembrance of the shoa with the way it is passed on”. 2. to remember, to repress To remember is a personal action, but also memories come over you. It is also a collective phenomenon. Who remembers whom where and how? Memory could refer to own experience or that of an other. Than the transmission gets a narrative, that could be believed or doubted. Also stereotypes and phantasmagorias like the Jewish world conqueror or the master race are passed on and last in memory. The generation of the posthumous, the children and grandchildren, are not beset with the memory of a direct experience of the horrors nor with questions of guilt. For them there exists the possibility to deal with the memories and happenings of the Shoa with more analytically, but also exists the danger of not really being affected. Those who survived remember things they can't get rid off any more; some tell about it. After 1945 Etienne van Ploeg rebuild for himself the place where he could not escape from, en miniature in a cigar box, “in a seemingly handy format,” as the explanatory note says, in Sachsenhausen, where it is now exhibited. Contemporary witnesses, who neither see themselves as victims nor as perpetrators, maybe have an easier approach? Did they suffered less? Are they able to overcome this? Or do they feel guilt and find tactics of to evade the subject? But than, when all of them, sometime do disappear? Maybe than the question is less one of the How of remembering, but one of the What of remembering: What is remembered? Of whom or what? If the experiences of the Shoa are no longer one's own any longer, who is than? Another concern is direct narration, for remembering cannot be confused with truth: “my granddad wasn't a murderer.*” Memory is overestimated. We should not so much say that we remember, but more question, how we do that. For the public is enough that we remember. „Unlike the German society the survivors can't evade from the experiences of humiliation and the memories of the crimes. Auschwitz and the extermination define their future. We are at the beginning of this discussion and yet are already at the end. Because with the death of the last witness of the extinction also the memory impends to die. Because with the death of the last witness of the extermination lies the danger of the death of the memory.” (8, The final insult ) (1) “Who hasn't been in Auschwitz never gets in. Who was there, never gets out.” Primo Levi It's not forgetting. To repress The deletion of the memory is rather an achievement/ability of the too awake consciousness than a weakness/debility towards the superiority of unconscious processes. Adorno says.(2) “The denial /negation is one way to take note of the suppressed, actually it is already an annulment / dissolution of the suppressed, but certainly no acceptance of the suppressed.” Freud (1968: 12) Many interviews were made with visitors during the exhibition: “Extermination war: Crimes of the German Army 1941 to 1944“, that was shown in many towns in Germany and Austria in the years 95 to 99. Many of them took part in the extermination war in the east as soldiers. The book “Dead zones” by Hannes Heer (3) shows us the complex distortions and formulations of their memories. An example: „Maybe the answers of the two witnesses are so fruitful, because they never before got tested through; instead they emerged out of the unexpected confrontation with what was thought to be finished long ago. They consistently confused concrete details as their own part of the crime, answers have a high value of information in the description of the general procedures of the crime: the interlock of military operation and terror caused by race ideology, which P. stutters (…). Beyond the affirmation that both interviews give to the historians, they are important because the narrators by stuttering and becoming silent, as it were with tongue bit through, reveal themselves as perpetrator more than in any other conversation. Apparently that correlates with the fact, that both wanted to forget the awful events of the war, but didn't forget de facto. By that, they are exposed unprotected to the sudden re-remembering. Instead of suppression (the keeping away from consciousness or the covering with fictive positive experiences), the cruel happening got stored in some “dark corner” of the system of memory. By mentioning an “unusual catchword” the access to this remote memory reservoir is suddenly there, the teller gets overwhelmed by the unsuspected and uncontrollable memories that were not known any more. The origin of such “vivid memories“, so Daniel Wright George Gashell, is owed to traumatic, in any case but meaningful happenings. (… ) Our two witnesses are able to remember, because the remembered belongs to their adult life. But because they didn't update it, it is fresh and unaltered as in the moment, when it occurred. Fresh and unaltered means – it carries all symptoms of a shock and the emotional confusion from the moment. These “involuntary memories” not just point at something past, they are also relived in the present.” (246 f.) These (hidden) stories of the perpetrators appear when there is a careful psychological attention. The traumatized, those concerned with guilt, and the dead: all keep silent. The gap to the next generation widens. Following generations have an incertitude about how the cruelties happened and who took part. There are memories from which repertoire stories are told easily and there are memories, that find their way unsuspectedly. I now leave the track of the claim of memory and start to get interested in pathology. Amnesia (Greek a „without, not“ and mnesis „memory“) is a condition in which memory is disturbed in time or contents caused by trauma, disease or brainwash. 3. to forget, to lose To forget: When the experiences are so grave, that surviving is possible only by forgetting. From the victims (4) we know more clearly this relocation of consciously suppressed to “mechanical“ forgetting. Forgetting as a Being-able-to-bear. When the experiences are played like sounds in a loudspeaker: Is the volume too high or the frequencies to strong or subtle, the device is not capable to reproduce them: The peaks of the high-amplitude sine-wave is simply not heard, the device is just transmitting blanks. It often makes a specific error-sound. For Hermann Schmitz forgetting is not a disappearing of the forgotten, but a change from name- and countable things into a chaotic multiplicity, carrots, potatoes and bacon become stew. To remember than is the fishing out of certain vegetables from the soup. „But the most important vehicle of the implication to the personality is to forget, which is not to lose, but a melting down of the experienced into chaotic multiplicity similar to the indwelling (healing) of wounds into the personality, that would without the forgetting crumble and could not always round anew and become a wholeness. The forgotten consolidates into seeds of the memory, which continues to effect sustainably as situations in the personality also without reproduction; besides that there is reproducing memory explicating singularities from the chaotic multiplicity of the forgotten.” So losing it is. So it is not the individual forgetting that is frightening us. Also forgetting is overestimated in this discourse. The lost is the actual threat. Forgetting could also be the only possibility to exist, an existential necessity: Trauma gets erased. The anti-fascist parole “Against the forgetting” doesn't seem to be the best demand. We shall remember? By / Through what? To keep the places in mind, the relics of the murdered, and the relics of the murders, how do they help us to go on? How far is the objective of the continual remembrance of the Shoa a part of the perpetrators intention to remember? 4. victims and perpetrators. Objects in museums In Prague in 1942 to 1945 the “Jewish Central Museum“ was established by Jewish scientists under the supervision and guidance of the SS and equipped with Judaica of the deported communities. „Shall we admit, that a historic story will unroll, it doesn't matter how a text is structured in particular, but where the order of the reconstruction of past by the narrative in the form of hi/stori/es by itself already affirms the discourse that made it semantically possible to national socialism to use terms like Endlösung and Endsieg?„beginning” (arché) means in old Greek polis also order, command; memory requires the imperative to recall, to be put in motion at all [Derrida, Archive fever]. The new configuration of the Jewish museum in Prague is in fact effect of an administrative order. (…) But cultural objects were packed, unpacked and catalogued as objects. (…) As data bank, museum depots are indifferent objects of record registries; the difference is made just by the intention, the discursive aim and direction of its use. With this a classical requirement of the media, the museum, is addressed: the one that differs from the pure non-descriptive storages/memories: the exhibition and the showing as discursive interface to the visitor, the addressee. (424 f.) (5) “We may be delegating to the archivist the memory works, that is ours alone. Thereby allowing memorials to relieve us from the burden of carrying memory.” (James E. Young) Hitler wanted to erect a memorial to the remembrance of the extermination of Polish Jews. We don't know, how it was supposed to look, but the stones where already in site. Dirk Rupnow writes: „As opposed to forms of propaganda and the practical realisation of the politics of robbery and extermination, the perpetrators' projects of objectification could not be clearly demarcated.” He quotes Nitzsche “All history is written up to now from the point of view of the success, namely with the assumption of reason. (… ) The question ‘what would have happened, if that and that would never have happened' is denied nearly concordant, but yet it is the cardinal question, by which everything gets to be an ironic thing”. The fact that also after a German final victory Jewish Museums, research institutes working with the Jewish culture, and memorials for the crime – understood by Nazis as a heroic act – could have been established and their field of memory (on the surface) couldn't be differentiated from ours today. This should have serious consequences for the view on our culture of memory today and should generate an essential disturbance. (338 f.) There seems to be a preference to remember than to cope with it. "Quand les hommes sont morts, ils entrent dans l'histoire. Quand les statues sont mortes, elles entrent dans l'art. Cette botanique de la mort, c'est ce que nous appelons la culture.C'est que le peuple des statues est mortel. Un jour les visages de pierre se décomposent à leur tour. Les civilisations laissent derrière elles ces traces mutilées comme les cailloux du Petit Poucet mais l'histoire a tout mangé. Un objet est mort quand le regard vivant qui se posait sur lui a disparu. Et quand nous aurons disparu nos objets iront là oÙ nous envoyons ceux des nègres, au musée." (Alain Resnais in: Les statues meurent aussi 5. identity One task of the remembrance is the construction of identity. Normally that is the memory of the winner, more exactly: the power. We are living in a culture of the perpetrator's memory. The Nazis didn't win the war, but the surviving victims are in a minority, so what dominates… , you know. Zifonum analyses collective memory with the aid of two memorial places: the one at the former concentration camp Dachau and the topography of terror in Berlin, where the former Gestapo headquarter was. His focus is the process of constructing identities. Zifonum names three types of remembrance in the German discourse of memory and calls them Betroffenheitsdiskurs, Schluß strichdiskus and Aufarbeitungsdiskurs (6) without choosing the words well: discurs of concernment, discurs of the final stroke and discurs of accounting for the past. (Zifonum ,133) (7) „While the discourse of the final stroke aims to forget the crimes of the national socialism and to a superseding of the memory, it tries to stop this motor. As a difference, the discourse of concernment starts with stigmatizing the victims, that is maintained to create sense with connecting presence and past sense with the victims. The connection of guilt to the crimes of national socialism is being extroverted in a provocative manner which integrates by this the crisis of sense into a construction of sense. The breach will be maintained and established and the self-stigmatizing argument with it is made to get the true core of identity.“ 227 „With the mode of ‘flipping stigma' an empirical grounded and theoretic consistent explanation for the paradox reasoning / explanation of German identity from the remembrance to the national socialism was presented. (… ) Jewish identity today frequently gets justified/explained by the reference to the holocaust, in Germany Jews get interpreted as victims, on which German identity is able to straighten itself, or but however as a ratification for a German improvement, uplift. (p. 226) As long as there is a perception from the perpetrators as being victims, an accounting of the past is impossible. „By the renunciation of a self-stigmatization to be a perpetrator the inhabitants of Dachau move either in a zone of an unsure stigma identity coined by the final stroke discourse or in the precarious identity based on the discourse of concernment – precarious because it is dependent on the acknowledgement of the former prisoners - which has the tendency to incline to the discourse of the last stroke. (… ) The crimes memorized in the topography of terror do not seem to fit in a history of national grandeur. By defining the places of the perpetrators it was possible to exclude an interpretation of the site in the way of concernment. Also the discourse of the last stroke turned out to be inferior in the competition with the offers of interpretation of the discourse of accounting of the past, because the discourse of the last stroke gets branded as the real problem of memory, i. e. as the starter of a “second guilt”. In both cases it proved to be that just such discourses generate identities, which, following the paradox structure of symbols, take the detour along the acceptance of a stigma of self-defence. Guilt is not at the end but at the beginning of constructing identity. It turns out, that the one you try to defend yourself from is creating the culture by changing value in the process of an “accepting defence” and meaning and identity are born.“ 224 f. A new chapter in the German culture of remembrance shows up after the fall of the wall. In Berlin the Jewish Museum, the memorial of the murdered Jews and the topography of terror, the place of the former headquarter of the Gestapo were all opened in a few years and show a big political interest in a public – official remembrance. If you look closer you see, that the Jewish museum is an institution that claims to be explicitly made by Germans and made for Germans, and which exhibition is telling mostly about the richness of former Jewish culture as apart of a German culture. Purchase and preservation of the power of interpretation: who owns it? The abundance of photos of the proud pose during the executions that were designated for wallet and family's photo albums, how you could see it in the Wehrmacht exhibition indicates the spectrum of the memorabilia. Remembrance replaces accounting of the past. Places get used to drop wreaths and create a national identity by incorporation of the victims and of being (getting) a victim. blankspace My friend Keren told me about a family album of a friend. Remarkably many of the photos from the Forties missing. That friend knew, that her father took part in the mass murder as a Nazi. He erased the photographic memory by their removal, but the blankspaces lasted like seats of honour in the album. 6. Memorials In the socialist countries memorials where monuments honouring heroes, martyrs, as part of the production of a glorious socialism. example Salaspils memorial: The over-size socialist figures of pathos are named „red front“ and „martyr“. Jews were not mentioned. The memorial consists of an empty area with Herculean figures. Tabula rasa, the history got reduced, simplified to founder figures of the own new history. „Things are getting forgotten, when the living view on them is vanished.“ Resnais says in „Les statues meurent aussi“. The statues also die. Mahnmale – there is no word like this in English: mark, stain, base to admonish. Mal is a commemoration. Memorials are in the place where the cruelty happened. They have something auratic inherent: the authentic. Some places get re-created, aura evoked, and a collective memory. Others disturb the existing. I want to talk about two proposals for the “Memorial of the murdered Jews of Europe”. Peter Eisenman erected it, but I'll introduce you to other proposals. Horst Hoheisel proposes the demolition of the Brandenburg gate. The Brandenburg Tor, designated to be the central symbol of German grandeur and unity, shall be destroyed and shall be squelched to dust, the site shall be sealed up. It's clear, that an outcry would go through the country, if the proposal would be asserted /accomplished/ realized. How many would be appalled, shaken up to their marrow, concerned from body to soul for this destruction of a cultural artefact. To which arguments one would cling, when confronted with the murder of millions? There has never been that much uproar about this disaster, as could be expected about the destruction of the Brandenburg gate. The Brandenburg Gate, coronated with the goddess of victory in a military vehicle, got damaged heavily in the war and rebuilt after anew. Barely one stone is authentic. The fact that such monuments get reerected, gets visible at the Frauenchurch in Dresden. I imagine, how with every switch of government, the gate gets erected again, the memorial gets destroyed, than the memorial again by destruction of the next gate-copy, completely in the idea of the Japanese Ise-shrine, that every twenty years gets destroyed and rebuild in exactly the same way. But if today monuments like the palace of the republic, the former main building of GDR is to be torn down, than with the intention to rebuild a new version of the old castle of the monarchie. The interest today is that on totalities, on rounded-up stories, breaches like they were (still) possible in the Sixties, the ruin of the Gedä chtniskirche in Westberlin, which was kept and juxtaposed with a contemporary, clearly separated new build(ing), and the debris of the bombed Frauen-church in Dresden, that got conserved as such and left as a memorial in the centre of town. Both are buildings, that do not have the violence that came from Nazi Germany as the topic, but on the contrary, consider themselves as victims of the allied bombing. Years before, in1987, Hoheisel was commissioned with the reconstruction of a fountain. „Umkehr des Aschrottbrunnens – reversal of the Aschrott fountain“. It was placed in the beginning of last century in front of the town hall of Kassel, then destroyed by Nazis, because it had been donated by a Jewish citizen. After the war the leftovers were covered up with flowers. Hoheisel rebuilt the fountain … turned it upside down. The waters now run down the funnel of the negative mould – all the way down to where the tip of the fountain reaches ground water. Ground water in Greek mythology is the Lethe, stream of forgetfulness (8). The plaza still seems to be empty, until you stand on the grating where you hear and see the water of the fountain. Horst Hoheisel: „The actual memorial is the passerby, who stands on it and thinks about why here something got lost.“ “The most striking thing about memorials is the fact, that you don't notice them. There is nothing in the world, that is as invisible as memorials“. Legacy at life time : Robert Musil Rudolf Herz and Reinhard Matz suggested to sell the site in central and touristy area of Berlin, that would have housed the memorial and with the money establish an institution against contemporary fascism. They relocate the memorial to the centre of Germany, near Kassel. They attack the autobahn which is “the vital core of the German people's fascination with the ‘Third Reich'.“ (Welzer 106)(9) One kilometre of Autobahn will be repaved with cobblestones, so that you are not able to drive more than 30 kilometres an hour. The typical blue motorway signs above reads “Memorial to the murdered Jews of Europe”. The place of the “dearest child of the Germans”, the place built by the Nazis and appreciated without a doubt since, would last in the public discussion. The design “would keep the passions alive, oscillating between guilt, aggression, studied tolerance and anti-Semitism in the manner characteristic of the overall German relationship to the circumstances brought about by National Socialism. ‘Take your foot off the gas, you German!' would indeed be a very mean thing addressed to the driver.” (106) 7. be concerened and come to terms A small-scale memorial project is „Stolpersteine – stumbling stones” (10): commemorative plaques in the size of little cobble stones made from brass. These are inserted on the sidewalks in front of the last residence chosen by the deported. The stones are inscribed with „Here lived… “, the name or names as well as date of birth and date and place of death. Since 2003 more than 10.000 stones have been inscribed. For 95 Euros a stone could be placed. After noticing few stones, we suddenly notice, that the deported lived in every neighbourhood, that they were neighbours everywhere, and they were not just a few. 8. to sense, to understand: art 1986 Luc Tuymans made a painting, that shows a sparse room in broken and washed out colours. The few things inside are hard to interpret. The painting's name is „Gaskammer“, gas chamber. The painting shows a chamber, how it exists today as a memorial. Luc Tuymans uses images to emphasize the gap between the knowledge of that what is represented, the remembrance, and the picture. „You shall not paint what you did not experience by yourself.” he says (11). He uses means of dissociation, as a reflexion and with the knowledge of the impossibility to convey the atrocity sensually. 9. images and the unrepresentable If we claim to say that the central endeavour of a memorial in our context is the hope, that the Shoa never happens again, so it is regarded as imperative to exercise the preconditions, that enabled it. Or is it possible, to ward off the danger by deterrence? By the representation of the unrepresentative? Is that so? Claude Lanzman avoided any footage from the time of the Shoa in his film of the same name. He even went that far, to announce that he, if he would discover photos from inside the gas chambers, he immediately would annihilate them. Prohibition of images (12). The power of images seems to be strong, iconoclasts are not denying the significance of images, quite the contrary. But doesn't this talk of the unrepresentable lead to an „aura of the holy horror“ how Rancière remarks (13)? The non-depiction if the direct crimes of the Shoa was already aim of the nazi-perpetrators. They showed, as we showed just now, interest to the historicity of the Jewish culture, as well as to the honouring representation of the goal of that crime: the extermination of the Jews, but the literal presentation of the photos, how they happened to end in family's albums, was forbidden with punishment. We have to cope with the images of the Shoa, accept them as part of our culture, as part of our image world. The picture is not identical with the depicted. We know and see the difference. But iconoclasts do not trust our capacity to do so. The unimaginable, it's not the one, we can't make an image of: the no-image, the non-representable, which isn't the same than the one without images, that does not have its own repertoire of images, but the possibility that we can insert our images, occupy it. But it is the one we can't fully understand. We can't get it. We can't grasp. 10. The photo of the synagogue In Kuldiga no picture of the Shoa exists. We have image memories of Auschwitz or the ghetto of Lodz. Just very few narratives of Kuldiga form our memorative expectations. We don't have preformed images as Auschwitz, which exists completely now as a symbol or a metaphor. ersatz images images of compensation of substitute images. There isn't barely any expressive images of the diverse Jewish life of town. I catched myself filling this gap with images, images from Chagall, a chicken. I see this chicken, how it on a Bar Mitsvah rushed into the centre of the hall, startled from it breeding place in one corner. I know it is not existing. It is false nostalgia. No little boy remembers the moment, clear like water, as he got an idea about the coexistance of people and languages by hearing the sounds from the street below. We are not remembering the girl, who's „Romeo and Juliet“ curls by the tears, also them couldn't cross the borders of their neighbourhoods. I try to recognize, which trees stood at the streetside of the synagogue: apple trees? Did you see Idi i smotry? „Come and see“, the film by Elem Klimow? How all inhabitants of the place get herded together in bestial ways in the holy house of the place (a church, not a synagogue, that didn't seem possible in the Soviet union in 1985) and get murdered. I can't keep away Elem Klimov's images from the synagogue here. Переходы is not so far away. I know, these images do not agree, are not authentic. They are – desperate or nostalgic – approaches to that that does not speak from (out of) images. Do we sense the losing? Do we sense the Unimaginable? (It's not un-imagine-able, and not un-think-able, but it is not understandable) Or do we simply do not imagine anything? It gets lost? We, the next generations are just not interested any more in really facing up to it? And how much defence is there still against the unimaginable, the extinctions in the neighbourhood made by the “liberators from the soviet occupants” and by the own neighbours, even by yourself, your own family. So we create new images? Boltanski says he is not making art about the holocaust but after the holocaust. Images, that help us here and now, to cope with Shoa as the one, drastic, far-reaching event in the history of the town of Kuldiga. 11. re-capitulation and end Re-capitulation: Every image, every memory is fragmentary. Totalities are mythic: they simplify, reduce. To speak with Finkielkraut: It's always possible, to use memory against forgetting. But what saves us from the memory that makes people willing, that brings their mind to sleep and strengthens their ideological certainty? To suppose, history can't repeat, if there is just enough remembrance, means to neglect and overemphasise the ability and functions of memory at the same time. It is not, that every coping with the memory automatically brings enlightment. To remind and to remember is one thing, enlightment an other. At any rate, memory privileges piety and consensus over freethinking and criticism. It tends to foreclose discussion rather than to unblock and encourage it. Timothy Garton Ash proposes the Mesomnesia, the middle way between Amnesia and Hypermnesia. About what we shall reflect, one shall think about? Which coherences shall be generated? How do we deal with the places of mass executions? How do we bring them to be sensed in town? How are the mass graves to be kept appropriate? Where are the names of the involved? All memorials are historical. The place of the synagogue as such, as place of the Shoa, how it just shows up to me in photos and narratives, in the negotiation of the Jewishness of the place in Soviet times, and today with the danger of being used as a producer of national identity. They are just valid in their time, in actualities. They all have an expiration date, it is just hidden. The perfect memorial is ephemeral: It just exists in the moment, again and again, always different. Disquieting presence. Mo(nu)ments, not those of Memory-tourist mistaking the story of the part as the whole. What we need is individual narrations. All outline for official memory must remain provisional. Memorials are not everlasting. Always they exist in a context, in time and space. The ambition should be to find the keys for every time, always new. end Depictions and narratives are our historic reality, which is part of the one past, that we, me, experienced. But isn't there a danger, that this as a self-sufficiency prevents dealing with survivors and the first hand. How those did experience it, can't hardly tell about it, because the reality is too harsh, those, who didn't experience it, could hardly tell about it with there after-life. Images by strong sensation both, but time passes and power wins. The nazis, as archetype of the evil or as chique look and promise of audacity boldness? What's important to us? Holocaust as an amplifier, like name dropping. The past is a transitory term, one of its borderline people is the ghost, the one who comes back, Wiedergä nger. When things that happened just don't want to rest in peace, end: the reappear, repeatedly. New answers for new questions in always other times. Memorative places are always time-bond, contemporary. They are : ephemeric. „I see the afterlife of the national socialism in the democracy as potentially more threatening than the afterlife of faschist tendencies against the democracy..“ Theodor Adorno : Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit 12. apodosis: Library to liberty “… because humanists don't start a revolution, but found a library.“ Godard says in his movie “Notre Musique” and with this quote I offer a first approach. While researching, it struck me that the amount of books of a small town library like Kuldiga's answers the number of books,burned in Bebelplatz by the Nazis: 20,000, for which Micha Ullman built shelves in his „library“. Ullman built a cube under the pavement 5 on 5 on 5 metres with shelves for these books that disappeared, closed off to the top by a glass that is flush with the ground. The library is empty. To imagine the dimension of it. The feeling of standing on an abyss, gap, when you look into the Ullman's memorial to the book burning, the cold of the neonlight and the sterility of its orderedness. Like a Noah's arch swimming in the Berlin ground water but the beings are dead. A house of death. „Ullman diggs, but does not bury or plant anything. The action of digging reveals. Pits like scars, that symbolize the impossibility of healing and puts the stamp of their missing inner identity on the earth. There is no conversation / talk? With those, that rest in the grave, solely the referral to unknown, nameless graves. The shelves of the library stay empty, though we know the names of the authors of the books being burned. By that, Ullman achieves a generalization beyond the actual event. The sealed space becomes a void, that contains pain, fear, doubt, memory, but also light and the potentiality of the word.”(14) Since 1990, there is in front of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, another piece by Ullman called: "Niemand" (no one): A cube from rusty steel, open on top but too high for anyone to see, filled with sand. It has certain forms at the sides recalling niches of houses, a bit like Rachel Whitehead's sculptures. It is an inversion of the library coinciding with one of the proposals in this symposium: to make a wall around the synagogue: We all are excluded. Maybe a centre of translation? Many important books, that deal with the reasons Nazi fascism was possible. So translations of Goldhagen's „Hitler's willing perpetrators“, Theweleit's „Men's phantasies“. Adorno not even has a hit in the Latvian Wikipedia. It's not so easy to fit the program of a library into that of a synagogue, neither into that of a cinema. Stronger floors are needed to hold books than people. Books should be stored in dry places, but this building has no isolation. Much light is needed for reading, but darkness is needed for the preservation of books. There are no divided room for storage, personnel, etc. And it is cheaper to build a new building than to restore an old one, especially when its function is changing completely. But there are financial reasons to put a library here: a European funding pays new libraries in Latvia. So the town gets a new building where a ruin stands: killing two birds with the same stone. Resnais in his film about the French National Library said, that books are kept there like in a prison: There is just an in, no out. He also asks if “books are the true witnesses of a civilisation. The time when all the enigmas are solved, when the universe gives us its key, and we sit on all its pieces of the universal memory to put together piece by piece the fragments of the one and the same secret, that maybe has a good name that is: luck.” But it could also be dread. Rémo Forlani: “When you don't forget, you can't neither live nor act. The Forgotten has to be construction. It is necessary, on the individual as on the collective plan. That, what you always have to do, is acting. The desperation, that's the non-acting, the folding-in-yourself. The threat is to stop yourself.” For many days, probably 1000 Jews awaited here for their murder, inside roughly 350 square meters, that means three had to share one square meter. You could not even lie down to sleep, this being less than the space of one cinema seat. Can we bear a library in a haunted space? (1) The final insult – das diktat gegen die überlebenden. Gruppe offene rechnungen (Hg.) unrast (2) „Erziehung zur Mündigkeit“ of Theodor W. Adorno, Frankfurt am Main 1971, S.14 (3) „Tote Zonen- Die deutsche Wehrmacht an der Ostfront“ by Hannes Heer. Hamburger Edition des Hamburger Instituts fü r Sozialforschung, 1999 (4) (Rudy Kennedy:) The death march lead to Gleiwitz. We had to drag ourselves there where we got loaded on a train and me and the others got brought to „Dora“ work camp. Later, as I drove the road by car, I was wandering, because I remembered just one day of march, but with the car it took hours. It was impossible to make it in a day. I found out, what really happened there, only when I met (… ) Hans Frankenthal on a meeting with other surviving slave workers of I. G. Farben. He told me, that we had to walk for more than a day. In between we stayed overnight in a barn and it was very cold. Many dead were lying around us and we laid under them, not to freeze to death. Up to today it is deleted from my memory. I cannot see it, I can't recall it. My brain simply kicked it out. But all that has happened. It was that traumatic, that my memory/remembrance erased it.“ S.79 f. in: The Final Insult (5) „Im Namen der Geschichte: Sammeln – Speichern – Er/Zählen: Infrastrukturelle Konfigurationen des deutschen Gedächtnisses“ by Wolfgang Ernst. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, München 2003 (6) More vague, but closer to the common parlance Adorno is: „Mit Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit ist in jenem Sprachgebrauch nicht gemeint, daß man das Vergangene im Ernst verarbeite, seinen Bann breche durch helles Bewußtsein. Sondern man will einen Schluß strich darunter ziehen und womö glich es selbst aus der Erinnerung wegwischen. Der Gestus, es solle alles vergessen und vergeben sein, der demjenigen anstü nde, dem Unrecht widerfuhr, wird von den Parteigä ngern derer praktiziert, die es begingen.“ Theodor Adorno : Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit (7) „Gedenken und Identität- Der deutsche Erinnerungsdiskurs“ by Dariuš Zifonum. Campus Frankfurt am Main, New York 2004 Fritz Bauer Institut. (8) Lethe, the name of the river means „forgetfulness“ or „concealment”. The greek word for “truth” is a-lethe-ia, that means „unforgetfulness“ or „unconcealment“: The belief was that the one who drinks from the water of the Lethe forgets his memories. Some believed furthermore that the souls had to drink from the stream, before they got reborn, so that they couldn't remember anything of their previous lifes. (9) “Kunst als soziales Gedächtnis” by Harald Welzer, in: „After Images – Kunst als soziales Gedächtnis“, Neuen Museum Weserburg Bremen, 2004 (10) Initiator of the project is artist Gunter Demnig www.stolpersteine.com (11) whole article (12) Damnatio memoriae is the Latin phrase literally meaning "damnation of memory". It means the total extermination of the remembrance and honor of a person. The term though is not of antique origin, but a modern invention. The names of especially dispised, hated people got erased in all files, annals; every representation and inscription in reach got destroyed, and for the future it was avoided at all costs to mention just anything concerning the condemned. All these actions were meant to lead to a complete forgetting of the one. (13) With the video„The Game of Tag“ of Artur Żmijewski (1999, Courtesy of Artur Żmijewski and Peter Kilchmann Galerie, Zürich), which is shown right now on Documenta, and which shows naked people in a childrenlike, cheerful game of tag in a bare room, that turns out to be a gas chamber in Auschwitz, the artist insists on the wish of having a bearable version. see images (14) Micha Ullman – Bibliothek. p. 95. Published by Friedrich Meschede. Amsterdam, Dresden: Verlag der Kunst, 1999. |