whole lecture in German

translation to latvian

Introduction

The subject of my lecture is what the American novelist Saul Bellow laconically described as the German's "sudden sensitivity about evidence".

In his travelogue >To Jerusalem and back< Bellow writes about relatives who lived in Riga under German occupation. During this period one of his cousins and her sister were slave labourers in a factory that made uniforms for the German Army. When the Nazis started to withdraw from Latvia in fall 1944 the two women and other prisoners were forced to open mass graves in the urban area of Riga and to burn the corpses of thousands of victims, most of them Jewish civilians, who had been shot by Germans and their local henchmen. The younger of the two Jewish sisters did not survive the work. She became sick and died under circumstances the author did not recall. (1)

The German perpetrators named the events that Bellow refers to as "Aktion 1005" - >Operation 1005< or "Enterdungsaktion" - >Reburial-Operation<, both code words for the systematic destruction of any trace of their mass murder in Central and Eastern Europe during World War II.

In contrast to the large amount of literature about the Holocaust, the destruction of evidence has seldom been the subject of historical research. In comprehensive representations of the Holocaust - e.g. the works of Gerald Reitlinger, Raul Hilberg, Leni Yahil, Saul Friedlaender and Peter Longerich - the >Operation 1005< is either shortly summarized or not mentioned at all.

One can, however, find a remarkable exception in the field of art. During the editing of his film >Shoah< (1985) Claude Lanzmann decided not to begin with the inauguration of Hitler or the NSDAP in 1933, with the preparations for mass murder in Germany, or with the SS-unit's slaughtering in occupied Eastern Europe or in the death-camps, but with the covering up of evidence in the Polish village of CheŁmno and in Ponary, a site of mass-executions near Vilnius. I assume Lanzmann made his decision not only because he realized that there is little filmed documentation of German mass murder but also because he recognized that some of the difficulties in representing the Holocaust originate from the fact that the perpetrators made a huge effort to wipe out the traces of their crimes and to kill all witnesses. Consequently Lanzmann opens his film with the nothingness the Germans created and shows the painful attempts by survivors who try to articulate the biggest catastrophe in Jewish history.

In one of the first scenes of >Shoah< Simon Srebnik, one of three men who survived CheŁmno, stands on the edge of a meadow that does not show that it once was the >Waldlager<, the camp-section where the gas-trucks arrived with the murdered Jews. Srebniks first spoken sentence shall be the motto of the lecture, he says: "It's hard to recognize, but this was the place." (2)

Part 1 -Synopsis of "Operation 1005"

My lecture consists of two parts. In the following I will give a short synopsis of the history of >Operation 1005< and in the second part I will speak about the destruction of evidence of mass murder in Riga.

The preparation of >Operation 1005< can be retraced in outline to January 1942. That is to say that the sensibility of some Germans was not without it's precursors. Contemporary sources or military orders have not been passed on, though this is hardly surprising. The aim during the destruction of evidence was to ensure that no additional evidence should emerge.

The task of leading >Operation 1005< was given to Paul Blobel, a long time Nazi-activist and skilled commander in the war of extermination against the Soviet Union. On January 13 1942 Blobel was released as commander of the Special Squad 4a (Sonderkommando 4a) and after a short meeting with Reinhard Heydrich in Warsaw, was sent to Berlin for further instructions. There, Heinrich Mueller, the chief of the Gestapo, informed him of the details of his task. Blobel was also obliged to observe the secrecy of his occupation. Just as the mass murder in the extermination camps, >Operation 1005< was supposed to be followed as "Geheime Reichssache", a top secret matter of the Reich. The code "1005" that was already being used by the end of February 1942 came from the reference number of the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt) the bureau that commissioned Blobels task.

After his instructions in Berlin, Blobel and his driver Julius Bauer went to the Polish city of Łódź. The city was chosen as a temporary base because of its proximity to the extermination camp CheŁmno. For reasons of secrecy, Blobel did not open an office of his own, but for temporary assistance, he asked for two members of his former unit, Franz Halle and Wilhelm Tempel. During the summer of 1942 Blobel stayed several times at the >Waldlager<-section of CheŁmno to test the cremation of corpses. The local camp guards were also interested in Blobels experiments, as he knew something about flamethrowers and incendiary bombs from his experience as a combat-engineer in World War I. Due to the summer heat, the corpses of the victims who had been buried hurriedly in mass graves, had become a hygiene problem. While there was little emotional concern expressed for those that were murdered, there was, however, a great deal of distress over the risk of the corpses affecting the quality of the surrounding water.

It was not only the temporary nervous men of the Special Squad in CheŁmno who wanted to benefit from Blobels experiments. On September 16 1942 the commander of Auschwitz, Rudolf Hoess and his employees Walter Dejaco and Franz Hoessler arrived at >Waldlager<. Blobel told them that during the cremation of exhumed corpses, one had to take care to pile up wood and corpses alternately. He also stated that the remaining bones could be ground up in so called "ball-mills" (Kugelmühlen) which the company Schriever & Co. from Hannover would naturally deliver to Auschwitz.

Moreover there are indications of contact between Blobel and Christian Wirth, the inspector of the extermination camps Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka, where the exterminators also started complaining about operating troubles in summer 1942. According to a testimony of Franz Stangl, the former commander of Sobibor and Treblinka, the idea of burning corpses on grates made from railroad tracks came from Paul Blobel. Finally Wirth modified the process of extermination in this three death camps: more gas chambers were built, special places to cremate the corpses of the suffocated were created and all the dead that had been buried during the first period of extermination had to be exhumed and burnt. Jewish prisoners from the camps were forced to work at the pits and the pyres.

The commanders office from Auschwitz utilized Blobels methods only temporarily. They did so during the cremation of approximately 50.000 buried dead between end of September and end of November 1942 and also in summer of 1944 during the murder of Jewish men, women and children from Hungary. Due to the huge number of deportees, technical problems ensued in the four combined gas chamber-cremation plants from Birkenau. In Auschwitz Jewish prisoners also had to work at the pyres.

In June 1943 Blobel gathered the first 1005-unit in the concentration camp Janowska in the Galician town of Lvov. The Germans managed Janowska simultaneously as a forced labour camp, as a transport stop-off to the extermination camps and as a site for mass executions. The huge majority of the prisoners were Jewish men, and it was mainly Jewish civilians who were shot and buried hurriedly by the Germans in "Piaski", a quarry-area near to the camp and in a forest east of Janowska.

In contrast to most of the other sites of >Operation 1005< we can get an approximate image of the living conditions of the 129 Jewish men from the so called "Death-Brigade", who were forced to burn corpses in Janowska and its vicinity since June 15 1943. Information concerning the destruction of evidence does not solely originate from palliative post-war testimonies by German perpetrators, but from surviving prisoners of the Special Squad who revolted against the guards on November 19 1943. Twelve of the men who escaped survived till the end of the war. One of them, Leon Weliczker-Wells, composed a detailed account of the "Death-Brigade" that was published in the United States, France and the Federal Republic of Germany at the beginning of the 60s.

The perpetrators scheme for >Operation 1005< in Janowska was utilized, with only slight variation, for all other sites of the 1005-units. The uniqueness of the camp, however, resulted from the fact that in addition to the destruction of evidence, training courses on cremation techniques were held there.

Usually Blobel or one of his deputies - Arthur Harder, Hans Sohns, Friedrich Seekel and Paul von Radomski - visited the commanders of the Sipo and the SD (KdS/BdS) or Himmler's Senior Commanders of the SS and Police (HSSPF) and gave them the oral command for the extinction of mass graves in their territory. Subsequently the 1005-units were assembled from several officials of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst) and a larger section of policemen. The SD-members either knew the locality and extent of the graves that had to be erased or got this information from the local Sipo-offices. The policemen, who were regularly briefed on the subject of their work after their arrival, were used as guards. They sealed off the working areas to keep people passing-by away, and to prevent prisoners attempts to escape. Before the beginning of their engagement, all members of the 1005-units were obliged to observe the secrecy of their work. The engagements were technically guided by the SD-officials. The commanders took prisoners from local jails, concentration camps, ghettos, forced-labour-or POW-camps for the work at the mass graves. According to the particulars of each project, the groups of prisoners consisted of several men or - in the case of Babi Yar near Kiev - more than 300 prisoners. In Kaunas and Ponary several women were among the prisoners who had to cook and clean the caves. None of the women survived.

The commanders had been instructed to chose Jewish men in the first place and to use non-Jewish civilians or prisoners of war only in exceptional cases. At the sites the prisoners were forced to open the graves with shovels and to pull the corpses with metal hooks out of the pits. In some cases the prisoners had to do this with their bare hands. Then they were forced to carry the corpses to the pyres where the dead were piled up with layers of wood. These piles were poured with oil or gasoline and in some cases supplied with incendiary bombs before they were set on fire.

Subsequently the workers had to sort valuables like jewellery or golden fillings from the ashes and to grind the remaining bones. The ashes were buried, poured into rivers or scattered. At the end, the prisoners had to fill the pits with earth and to level and plant the surface for camouflage. The destruction of evidence of these mass graves was done by the division of labour, and partly mechanised, in relation to the number of the sites. At several sites excavators were used additionally to open the graves and the remaining bones were grounded in motorized ball-mills.

All commanders of the units had been instructed that the workers had to be shot as witnesses at the end of the engagement.

The prisoners were guarded permanently, had to work in high speed and were kept on tenterhooks or deceived about their future. At some of the sites it was not possible for the workers to wash themselves or to change their clothes. In the testimonies of survivors examples of utter desperation and blackest humour can be found. (3) After several workers escaped in Lvov and Kiev all prisoners of the 1005-units were chained by their feet. After the end of their daily work the Germans locked them up in local prisons, sealed buildings near the working areas or in caves called "bunkers" with extra narrow entrance through which only one person could move at one time. There are several documented cases of suicide among the workers in the first days of their captivity. All men who were deemed sick, weak or injured were shot by the SD-officials, frequently on the pretext of medical treatment. During the executions at the end of the operations, the SD-and policemen worked together. The policemen sealed off the site, watched the workers and guided them one by one or in small groups to the place of execution. In several cases the prisoners had to take off their clothes and lay down with their face to the ground or to the prepared bonfire before they were shot in the neck by the SD-men. At the end their corpses were burnt too, in order to eradicate any trace.

Through site inspections, Blobel and his deputies informed themselves about the progress of the work. With the code name "weather-report" the commanders of the units transmitted the numbers of the burnt corpses as "cloud-ceiling" (WolkenhÖhe) through local Sipo-offices to the RSHA in Berlin.

Under German occupation, traces of the crimes were erased in several Eastern European countries. The work of 1005-units can be seen in today's Serbia, Ukraine, Belarus, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia and Poland. >Operation 1005< was implemented most intensively between fall 1943 and fall 1944. Beside units which were assembled only for a few weeks and whose members returned to their former offices at the end of the operations, there were several units which worked supra-regional respectively beyond national borders. For instance the Special Squads 1005 A, 1005 B and the Special Squad 1005-Middle which moved from site to site for almost a year.

With the decision for the systematic destruction of evidence of mass murder, the German leaders prepared for the eventuality of military defeat, which became evident in November 1941 when the advance of the German Army to Moscow was stopped by the Red Army. One only begins to care about destroying evidence when one starts to fear one's enemies strength, when you expect to be called to account for your crimes.

The practice of >Operation 1005< shows a mixture of rationality and mania that is typical for many German war crimes of that time. Someone who destroys evidence to escape punishment, to ease the sentence, acts as a criminal and rationally. Obviously the cremation of several tens of thousands of corpses on bonfires in open space can not be concealed from the local population. Therefore >Operation 1005< was far from being a top secret matter of the Reich. But one can not forget that the perpetrators made another calculation: a non-Jewish population that with few exceptions did not act when their Jewish neighbours were rounded up and murdered would also stay quiet during the cremation of the dead.

It is a remarkable tendency among historians who mention >Operation 1005< to characterize the work of the prisoners with adjectives like "unimaginable" or "inexpressible", though there are very detailed testimonies of survivors. Despite the work at the graves and burning areas, despite beatings and permanent danger of death, several prisoners escaped. In some cases after weeks of preparations, sometimes in the last moment, during their execution. Aside from the aforementioned outcries from workers in Babi-Yar and Janowska, prisoners escaped from 1005-units in Ponary near Vilnius, from the Fort IX in the outskirts of Kaunas, from the camp Borki near the Polish city of CheŁm, near BiaŁystok, near Polkovichi in Belarus and south of Belgrade in Serbia. Despite the German's intensive searching, several of the escaped survived in hiding places or joined partisan groups to fight the Germans.

Part 2 - "Operation 1005" in Riga

In January 1944 Paul Blobel met the Senior Commander of the SS and Police (HSSPF) Friedrich Jeckeln in Riga to discuss the preparations for >Operation 1005< in Riga and it's vicinity. (4) The unit Blobel sent in April 1944 to fulfil the task was called "Sonderkommando 1005 B" -Special Squad 1005 B. It consisted of 7 or 8 men from the SD and at least 40, possibly 50 German policemen who were commanded by Otto Winter.

This Special Squad had been lined up in Dnepropetrovsk during August 1943 by Hans Sohns, the coordinator of the >Operation 1005< in Ukraine. The place of assembly indicates that the unit, whose first commander was Hans Zietlow, was designed for the destruction of evidence in eastern Ukraine. For the western part of the region Sohns assembled a second unit in Kiev, the Special Squad 1005 A.

Together, these units erased the traces of mass murder in the ravine Babi Yar near Kiev. They forced a total of 327 Jewish and Non-Jewish prisoners to open graves and to burn several tens of thousands of corpses, most of them Jewish civilians, who had been shot since end of September 1941. Men of the Special Squad 4a that was commanded by Paul Blobel had been among the perpetrators, so Blobel had a personal interest in this engagement. However the extinction of traces in Babi Yar did not go totally according to the plan. In the early morning of September 29 1943, immediately before all the corpses were burnt, some of the workers escaped from the cave in which they had been imprisoned during the night. 25 men escaped in small groups, 15 of them ultimately broke through the barrier of the ravine and got out of harm's way. The rest of the workers, at least 250 men, where shot by members of the Special Squads.

After the destruction of evidence in Kiev, the men of Special Squad 1005 B worked in the Ukrainian town of Krivoi-Rog. Subsequently the unit went to Nikolayev where at least 30 Jewish prisoners were forced to open mass graves and to burn more than 3.000 corpses. The workers were shot in the second half of December 1943, the members of 1005 B celebrated the end of the work with one of their social evenings called "Kameradschaftsabend".

After a short break between Christmas an New Years Eve 1944 the unit was assigned near the Ukrainian village Voskresenskoye, east of Nikolayev. At least 10, possibly 15 prisoners had to work at the graves and bonfires before they were shot by the Germans and burned.

Apparently the erasure of mass graves was considered normal work in Nazi-Germany. Work that included vacation time. Therefore the unit moved at the end of January 1944 from the southeast of Ukraine to Poland and spent four weeks in the High Tatra mountains where some of the men went skiin. It seems that after the winter holidays further engagement of the Special Squad 1005 B had been planned for the south of Ukraine. These projects were eventually cancelled because of the constant advance of the Soviet Army, so Blobel directed the members of the unit to Latvia, a working area that seemed to be safe. There the composition of the unit was slightly changed. Fritz Zietlow was released as commander, his place took Walter Helfsgott, a skilled SS-killer who had chased partisans and hidden Jewish civilians with his Ukrainian henchmen before he was called to take part in >Operation 1005<.

After their arrival in Riga in April 1944 Helfsgott and his men were accommodated near the concentration camp Salaspils. There, Jewish men who had been deported from Germany to Riga, were forced to build the first shacks for prisoners in December 1941. Approximately more than 25.000 people were kept there at the same time in a total of 45 shacks. During the first months Salaspils was managed solely as a death camp for Jewish men from Germany. Since May 1942 together with these thousands of "Reichsjuden" - Jews from the German Reich - several thousand Latvian political prisoners were kept in the camp. The number and composition of the imprisoned changed again in summer 1943, when the Germans brought Latvian families to Salaspils who were suspected of acts of resistance. The guards of the camp locked children up to the age of five in a special shack, several hundred of these infants died during their custody.

The commanders office of Salaspils used the system of different classes of prisoners which was typical for the German concentration camps as an additional instrument of their command. In shacks that 200 Latvian prisoners had to share usually 400 Jewish prisoners were crammed.

Besides the concentration camp, a camp for Soviet POWs was located in Salaspils. In the fall of 1941 the first soldiers were locked there in old barracks, later the Germans kept them in two open sites which were fenced with barbwire. The estimated number of POWs in the end of fall 1941 is several tens of thousand, in June 1942 only 3.434 of them were still alive. (5)

The members of the Special Squad 1005 B used the localities of the camp guards from Salaspils for accommodation. The commander of the camp, that was officially designated as "work-correction-camp" (Arbeitserziehungslager), at that time was Kurt Krause who was subordinated to Rudolf Lange, the Commander of the Sipo-SD (KdS) in Riga, and with Lange Helfsgott discussed the details of >Operation 1005<. The two officials localized the mass graves in Riga and its vicinity and agreed that exclusively Jewish prisoners should be used for the work at the graves and the pyres. Lange would supply them from his camps and prisons. They also agreed that the prisoners should be killed, as they were witnesses to the destruction of evidence.

The Special Squad's first working site was located in the forest of Rumbula, in front of the city station of the same name, beside the main street to Daugavpils. At least 23.000 Jewish men, women and children from the Ghetto of Riga had been shot in that forest within two days in November/December 1941 by German perpetrators and their Latvian helpers. Unlike the executions of November some of the Jews who were forced into the forest in December succeeded to escape the German murderers. Together with Ella Madalje, Frida Michelson and the married couple Lutrins, Beila Hamburg survived who was just twenty-two years old at that time. (6)

About 2 and a 1/2 years after the mass murder in Rumbula the Special Squad began it's work at the site that was overgrown by plants again. From the end of April to around the first days of June 1944 at least 30 Jewish prisoners who had been handed over by Langes command had to open several graves in the forest. Temporarily, Helfsgott used an excavator that was driven by Walter Fiedler, a member of the unit. The workers were forced to pull the corpses with metal hooks out of the pits and to arrange them alternately with layers of wood to huge bonfires that were poured with burning fluids like oil or gasoline before they were set on fire.

After the cremation and according to the usual procedures of >Operation 1005< the workers had to sort all valuables from the ashes, to grind the remaining bones and finally to scatter the ashes. The workers were chained by their feet night and day.

According to the testimony of Walter Helfsgott, Blobel came to Riga a several times to examine the work of the Special Squad. Helfsgott also stated that Blobel was accompanied by Paul von Radomski who was in charge of the coordination of >Operation 1005< at the northern part of the front since March 1944.

In the trial of Hans Sohns and others 1969 in Stuttgart the judges were not able to ascertain the period of the destruction of evidence in Rumbula and the number of burned corpses precisely. In their judgment they did not agree with the assessment of the prosecutor who stated that 40 to 50 prisoners were forced to burn between 12.000 and 20.000 corpses of all ages from at least 6 mass graves. (7) It also remained unclear if the SD-men of the unit shot the workers after the evidence in Rumbula had been erased or if they took them to the next site.

This second working site of the Special Squad was the forest of Bikernieki, east of the old city of Riga. There Helfsgott's men moved into shacks which had been built by prisoners of the concentration camp Salaspils. The work was finished in the middle of May 1944 and supervised by two members of the unit, Fritz Kirstein and Hermann Kappen who was a skilled joiner. The same prisoners were also forced to dig and fortify a cave in which the prisoners of Special Squad 1005 B were pushed after work. Looking back Hermann Kappen draw a remarkable mental picture of this construction work:

"During our engagement in Riga I was set apart as a joiner to build shacks. Jews from the huge Jewish camp near Riga were used as labourers. They could move around quite freely. They were guarded by our foreign volunteers. [...] I can remember now that one of the working-Jews who belonged to the unit was assigned to me for building a small shack. He came from Dortmund. Ostensibly he was the owner of the coffee trading house >Kairo<. At the end of the engagement he was shot at the big burial-place. A comrade of mine gave me his regards." (8)

So in Kappen's sentimental post-war version, the only thing that is left from the murder of a Jewish prisoner without any rights, is just the regards of the victim to one of the perpetrators.

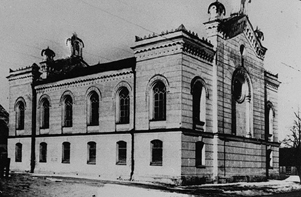

Immediately after the German Army occupied Riga on July 1 1941, Germans and their Latvian helpers used the forest of Bikernieki as a site for mass murder. The first victims were several thousand Jewish men who were arrested, tortured and finally shot in Bikernieki during July 1941 by Latvian militiamen, many of them belonged to the fascist organization PérkonkrÚst. For several months, KdS Riga units, the "Einsatzkommando 2" and the Latvian Special Squad Arajs, murdered in the southwestern part of the forest. Apart from Jewish men, women and children from Riga and it's vicinity thousands of deported Jews from Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia were shot. The exact number of those murdered is unknown. After the war a Soviet memorial in Bikernieki estimated at 46.500 murdered Soviet citizens. The fact that the huge majority of the victims were Jewish civilians is first mentioned on the Holocaust-Memorial that was inaugurated in November 2001. (9)

Between the middle of June and the middle of September 1944 the Special Squad erased the traces of the mass executions in the forest of Bikernieki. Two groups of at least 30 Jewish men were forced to work successively at the graves and the pyres. The men from one group were most probably from the Kaiserwald concentration camp that the Germans had established in the summer of 1943 between railroad tracks and the Viestura Street near the suburban district of Mezaparks. The men had been chosen for the work because of their youth and physical constitution. In Kaiserwald the Special Squad 1005 B was known as "potato-unit" (Kartoffelkommando) or simply "base" (Stützpunkt). The workers were forced to carry at least 20.000 corpses from the mass graves to the bonfires. Walter Helfsgott transmitted the number of the burnt corpses weekly to Lange, camouflaged as "wood reports" (Holzmeldungen). (10)

Evidently the Special Squad also took part in executions of prisoners of war and prisoners from concentration camps. About 500 disabled Soviet POW's and 70 to 80 prisoners from Salaspils who had been deemed unable to work were shot by a group of Germans - among them were Herbert Lange and Kurt Krause - in the middle of August 1944. The corpses of the murdered were finally burnt on a bonfire that had been built under the command of Walter Helfsgott. (11)

There is no information about the living conditions of the workers in the forest of Bikernieki. And in the files of the Sohns-trial the reports of their death refer just to the dates and circumstances of their executions. The men of the first group were directed to the execution site by policemen of the Special Squad and shot there by the SD-men of the unit at the end of June or during July 1944. At least 30 prisoners of the second group died in the same way at the end of >Operation 1005< in Bikernieki in the middle of September 1944. According to the conviction of the judges Walter Helfsgott stayed at the site during the executions but did not take part in the shootings:

"Certainly he [Helfsgott, J.H.] too considered the executions as unavoidable to keep the secrecy of the National Socialist atrocities and to preserve the German people from the enemies revenge. But it seems to be that he would have liked to avoid his personal involvement and presence during the executions and only took part in them because he thought to be bound on Dr. Langes orders and believed that a refusal would have deepest and perilous consequences. In any case Helfsgott endeavored to take part only on the side lines of the executions, for instance by dividing and supervising the cordons and things like that." (12)

The involvement of the defendant "on the side lines" of the executions that he considered as "unavoidable" was regarded by the judges as a sufficient reason for Walter Helfsgotts release.

Moreover the judges in the trail of Sohns and others were not able to ascertain without any doubt that the Special Squad erased traces of mass crimes in the concentration camp Kaiserwald before it's withdrawal from Latvia. But there are at least indications that members of the unit forced 40 to 60 prisoners of the camp to start the destruction of evidence at the mass graves near Kaiserwald. (13)

At the end of September 1944 Helfsgott and his men left Riga and were shipped to Gdańsk. There were many prisoners of the Germans on the ship too, probably from Kaiserwald. After the arrival in Gdańsk the majority of the female prisoners were brought to KZ Stutthof. The Germans pushed the male prisoners in "death-marches" (TodesmÄrsche) to different forced-labour- and concentration camps of the Reich.

On October 13 1944, Riga was liberated by units of the Red Army. The soldiers met approximately 150 Jewish survivors. (14)

In fall 1944 the >Operation 1005< ended for Helfsgott and his men but it did not end their engagement for Nazi Germany. They travelled by train from Gdańsk to Salzburg, were they were incorporated into a unit named >Iltis< - polecat - and fought partisans in the borderland between Austria and Yugoslavia under the command of Paul Blobel until the end of the war. Though the men of the Special Squad tried to work thoroughly they did not succeed in the destruction of all evidence. After the withdrawal of the German army from Latvia, units of the Red Army found remains of around ten thousand dead Soviet soldiers near the POW-camps in Riga, Daugavpils, Liepaja, Rezekne and Jelgava. (15)

In addition, at least the experience of one of the Special Squad's Jewish prisoners can be handed down. One of the men that were forced to work at the pits in the forest of Rumbula before they were shot and burnt by the Germans was Jehaskiel Hamburg. His wife Beila Hamburg was able to tell a part of her story before she died in Stutthof in February 1945. (16)

During one of the trials in Nuremberg Paul Blobel was sentenced to death and hanged in June 1951. He was convicted for his crimes as the commander of Special Squad 4a, not for his leadership in >Operation 1005<. From all the members of Special Squad 1005 B only Hans Sohns and Fritz Zietlow were sentenced for their actions in Federal Republic of Germany. In their remarkable judgement the judges wrote:

"One can not totally refuse to accept that the defendants conceived to act according to the interests of the people when they personally backed up the criminal plan of covering the traces through the extinction of mass graves and the killing of prisoners who were used for the work. In comparison to other racial motivated arbitrary actions which were committed during the National Socialist era this point of view does not allow to pronounce their civil degradation." (17)

For the present, Sohns and Zietlow were convicted to 4 respectively 2 years and 6 months penal servitude for aided and abetted murder in 280 respectively 30 cases. In August 1971 the punishment was changed to a sentence of imprisonment.

Footnotes:

(1) Bellow (1977): 129.

(2) Lanzmann (1988): 20.

(3) See Weliczker-Wells (1963): 194p.

(4) See Angrick/Klein (2006): 416.

(5) Informations about Salaspils from Verstermanis (2002): 478pp.

(6) For the names of the survivors see Kugler (2004): 219. Not least because of the ballyhoo subtitle "The Jewish SS-Officer" Kuglers well researched book reached the review sections of the daily papers and the recommendation desks of the big media stores. So for the further increase of media attention, in Germany only a Jewish KZ-commander and a Jewish Adolf Hitler will do.

(7) For their representation of >Operation 1005< in Riga Andrej Angrick and Peter Klein followed the bill of indictment in the trial of Hans Sohns and others. See Angrick/Klein (2006): 418p., 426p.

(8) Barch B 162/204 ARZ 419/62, Volume 2, page 499pp., interrogation of Hermann Kappen, February 21 1964.

(9) Information about the murder in the forest of Bikerieki from Gutman (Hg.) (1995): 1229 and Kugler (2004): 150p.

(10) These minimum-figures of the judges to the extintion of traces in the forest of Bikernieki distinguish clearly - like in the case of the extinction of traces in Rumbula - from the ascertainments of the prosecutor in the trial of Hans Sohns and others. According to the prosecutors investigation 50 to 60 prisoners were forced to exhume and burn 10.-12.000 corpses between the middle of June and the end of July 1944. At the end of the work they were shot. Subsequently another group of about 40 men had to exhume and burn another 10.-20.000 corpses in Bikernieki. Finally these workers also were shot by members of the Special Squad 1005 B.

(11) See Angrick/Klein (2006): 423p. who refer to a testimony of Erich Brauer, the former chief of administration in KZ Salaspils.

(12) Barch B 162/204 ARZ 419/62, Volume 6, Judgement page 76.

(13) See Angrick/Klein (2006): 427 where the authors refer to the investigations of the prosecutor in the trial of Hans Sohns and others.

(14) See Vestermanis (2002): 487, Gutman (Hg.) (1995): 1232.

(15) See Vestermanis (2002): 482.

(16) See Kugler (2004): 221f. The narrative of Beila Hamburg was written down by Abraham Bloch. See the extracts in Kugler (2004): 219-221.

(17) Barch B 162/204 ARZ 419/62, Volume 6, Judgement page 198.

Translation from German: Kasia Fudakowski, Jens Hoffmann

Files/Literature:

Bundesarchiv Außenstelle Ludwigsburg (Barch B 162/204 ARZ 419/62), 17 Js 270/64 Files of the trial on Hans Sohns, Fritz Zietlow, Walter Helfsgott and Fritz Kirstein, 19 Volumes

Angrick, Andrej/Klein, Peter (2006): Die "Endlösung" in Riga - Ausbeutung und Vernichtung; Darmstadt

Bellow, Saul (1977): To Jerusalem and Back - A Personal Account; Harmondsworth

Gutman, Israel (Hg.) (1995): Enzyklopädie des Holocaust; München

Hoffmann, Jens: Brände - "Aktion 1005", Auslöschung der Spuren von Massenverbrechen durch deutsche Täter; konkret, Hamburg 2008

Kugler, Anita (2004): Scherwitz - Der jüdische SS-Offizier; Köln

Spector, Shmuel (1990): Aktion 1005 - Effacing the murder of millions; in: Holocaust and Genocide Studies; Vol. 5, No. 2

Vestermanis, Margers (2002): Die nationalsozialistischen Haftstätten und Todeslager im okkupierten Lettland 1941 - 1945; in: Herbert, Ulrich/Orth, Karin/Dieckmann, Christoph (Hg.): Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager; Frankfurt am Main

Weliczker-Wells, Leon (1963): Ein Sohn Hiobs; München

|